|

Lockdown finally gave me the time to “just read a book”, something I’d been going on about for years. Although I do like reading, I think this idea also has an aesthetic to it that seemed comforting and involved many cups of (artisan) coffee, the smell of new books and the solidification of the type of woman I wanted to be; cultured, literary, articulate, educated.

The dream is well and truly within my reach now. I wear a linen dressing gown. I drink coffee from an arty, mustard-coloured mug. I have a rubber plant. I have several books piled up by my bed, a Moleskine notebook and even, yes really, copies of The New Yorker sprawled around, because I just left them there, half-open on that article about Syria. It’s really a shame no one is around to witness all of this. The problem is that, whilst I have all the dressings of the cultured, literary, articulate, educated woman I would like to be, I’m realising I can’t remember anything. I read books and, even when deeply moved by them (a valuable experience in itself) ask me what exactly happened or what it was about a week later and you’ll receive a vague, confused summary of some basic facts which, if questioned, I will not be able to explain. I’ll begin, enthusiastically, then backtrack as I remember something I should have brought up earlier, which only further confuses my listener. I feel Virginia Woolf turning in her grave as I describe A Room of One’s Own as “she’s basically saying women have to be really rich to write and even then, it’s hard cos of… the patriarchy…” I’ve started to wonder what the point of all this reading is if I’m unable to remember any of it. I thought I would have more brain space to actually comprehend and recall information throughout this time, but this inability to remember anything seems to have gotten much, much worse, spreading into my everyday life like a certain pandemic. Because I am a millennial I googled it, which is probably the real cause of why I am unable to remember anything, because I literally don’t need to anymore. Of course, I find an article about this, of which I will no doubt offer a long-winded, distorted explanation of to my partner tonight. Lucky boy. In The Guardian Julia Shaw, a psychological scientist at University College London, says of lockdown memory loss and confusion, “Our internal timelines, our autobiographical memories, need a “before” and “after”, or what memory researchers call “temporal landmarks”. These landmarks allow us to organise our lives into a story. Any good story relies on a narrative arc of emotional highs and lows, rather than a flat line of emotions and events.” So the mundanity of our current existence is blurring our memories, leading us to lose track of what happened yesterday and what happened last week. She continues: “If we don’t have suitable landmark memories, we are more likely to mistake what we did in the past. As time passes, this may even allow more room for memories of events that we never experienced at all. As a false memory researcher, this worries me.” It worries me too, Julia. It worries me because you’re suggesting that not only am I going to confuse what’s actually happening, I’m going to start making it up, presenting dire consequences for the legacy of Virginia Woolf. As much as the temporal sameness of lockdown is making the act of remembering more complicated, it also seems to me that as adults, we are expected to read the latest non-fiction book or article and recall its main points word for word. At school, the recalling of what we’d read was something to be practiced daily and tested annually (now more like biannually, or monthly) in exams. It’s not as if I graduated and the reward was that my memory unlocked a new mode, sponge mode, in which every fact I read was imprinted on my mind forever. This, unquestionably, would have been much more useful than my Creative Writing degree. Today we are the recipients of an unrelenting bombardment of information. Alongside the latest bestselling polemics there’s 24 hour news, podcasts, documentaries, TV shows, stand-up, the list goes on. Whilst this is brilliant and undoubtedly more interesting than my Year 9 Maths classes, it’s also undoubtedly more information than my Year 9 Maths classes, and I wasn’t very good at remembering these. Before we start considering if I have a medical problem, I should state that I do have an almost photographic memory of essentially non-intellectual things. I remember people, their faces, mannerisms, the way they speak, but not their names. I remember places, their point of entry, how they looked, felt, smelt, the noises they made, but not their exact location or how to get there. Often in my mind I see a place, an image of it, usually from the same angle, always with the same weather or in the same light. Memories are attached to these images. I think of conversations I’ve had with my best friend and see her block of flats in my mind, the road outside of it, the rainy weather from my first trip to visit her there. When I think of my parents I see the entrance to their living room, it is morning, someone can be overheard in the kitchen. Work is the view from my desk. It is hot, as it was when I started the job last June; the broken fan jutters in the corner. This extends, sometimes, to intellectual things. When I think of a book, I can often visualise the place in which I read it the most. This place comes to mind when I think of it, even if the details of the book itself are fuzzy. This type of memory, my next Google search led me to find out, is called ‘iconic memory’, i.e. the memory of visual stimuli, the image you “see” in your mind’s eye being the iconic memory of that visual stimuli. Despite being described as fleeting or momentary, to me these memories are the most concrete. These images allow me to anchor my understanding of the world to things, spaces, people. Facts, solutions and analysis elude my mind, whilst the sensory impression beds in, waving them off. This memory of place is also referred to as ‘place attachment’, where an emotional bond is created between a place and a person (although there is little information available on what qualifies a place to be worthy of place attachment, this value judgement being subjective). There are of course, simple explanations of left and right brains and logical and creative types to underline why I am not able to remember facts in the way I can remember sensory information or emotional things. The problem, I find, with creativity, is its wishy-washy looseness. To be good at creativity is very different to being good at remembering facts and information. One requires an interpretation of sensory information, relationships, societal pressures, tones, prejudices, to be processed sensorially and emotionally and put out into an artistic, sometimes entertaining (hopefully) form, that brings some insight emotionally or sensorially, through your unique perspective. In order to succeed at this, it should be original, it should be aware of and impacted by previous influences but not copy them; ideally it should move us. The other requires you to hear information and for you to remember it and for you to recall it, perhaps also recalling some other facts to further back it up and strengthen your argument. I’m not trying to demean or belittle that skill, of which I have very little and of which I am evidently jealous of, but the process is less complicated. Less, I think, is expected of it and yet, the outcome is still largely valued above and beyond any creative outcome, which is increasingly viewed by our government and education system as an optional addition to the curriculum, an “enrichment activity”. For this reason, I greedily want both qualitative and quantitative. And I know, bitterly, that there are people who are effortlessly both. I had a friend at school who would slip us the answers to the weekly Science quiz, swanning off to paint her masterpiece in Art, ending the day by eloquently breaking down the emotional and historical significance of Wuthering Heights before picking up her A* maths results. I want to be effortlessly both, but I will always be straining. She is six foot and I am five and we are both aiming for the same object on the same shelf. It will inevitably be harder for me to get there. Perhaps the fact I can come up with shelf metaphors for this struggle on the way is something to hold onto. For my own predicament, I am approaching the recollection of facts as an enrichment activity. I say I have decided, but really I have no choice, my brain has resolutely decided to retain instead the image of the two competing off-licences down the road, the scrawled handwriting on the knock-off hand sanitisers and their vendors; one short, stocky, with a hearty laugh, the other slim, quiet, respectful, calm; over the various statistics in The New Yorker, the key dates and times of the Syrian crisis, the complexities of Brexit negotiations. I have begun to write down the facts (in my Moleskin notebook), to at least try and recall them as I did in school; cover them with my hand and frown as I search for the percentage, the location, the name of the politician. While I muse over what that couple were arguing about in the park, I hope to enrich my imaginings with some facts about gender politics and what role this might play in this couple’s lives. If not, at least I can better fit my linen dressing gown, better explain my copies of The New Yorker, better preserve the works of Virginia Woolf. Or, worst case scenario, I can just Google it.

6 Comments

Queueing for the local supermarket in lockdown reminds me of being ten years old, waiting to go on a waterslide called ‘Apocalypse’ or ‘Annihilation’ or something equally reassuring. The nonchalance of the queue baffled me; draped over railings or play fighting on the steps, we all waited to plunge toward the ground at ninety degrees. I found the nonchalance reassuring; lots of people went on this slide, some of them had even come back to do it again. It was normal, there was nothing to be frightened of.

Here at the supermarket, there is more to be frightened of. Outside, we’re kept two metres apart by black and yellow tape and an English deference to rules but inside, we know, it’s a free for all. Who knew who had touched what or whether there was an infector stood behind you, breathing in your ear as they passed. Perhaps they touched the exact same Pot Noodle you decided to pick up. They’d fingered that expensive bottle of wine and decided against it, just like you, before releasing that cough they’d tried to suppress on the very same self-service machine you yourself had decided to use. This kind of thinking is even more pointless than fretting about falling out of the water slide and cracking your head, because unlike the slide, there is no choice of whether or not to eat. If you have the privilege of being unaccompanied by screaming children, demanding chocolate on entry, the supermarket used to be a place to be aimless, to linger: free to enter and open to all. Unlike other shops, where eager assistants beg to help you (pressure you), supermarket assistants are busy restocking, scanning, packing, cleaning. They have no time to ask you what you want or persuade you to try the latest cereal. They don’t need us, we need them, which in turn allows us to pack and unpack our baskets, return three times to the dried foods isle, inspect the nutritional value of various cheeses and google the ups and downs of non-dairy milk. But more than this, what makes a supermarket so enjoyable is that a person must eat, so to spend here is not to feel guilt about it. Unlike the clothes shop, the book shop, the bougie scented candle shop, to spend at a supermarket is a necessity that no one is criticised for. Now of course, there is no time to return to the dried food isle. If you forget something, you must disrupt the carefully managed conveyor belt of people and suffer the glares of your supermarket successors, as their successor turns a corner to see their predecessor waiting for their predecessor, all of whom watch you greedily grab another can of tinned tomatoes. It is a supermarket pile up, and you are the drunk driver. You foolishly chose a basket instead of a trolley and are now kicking it along the floor (collecting who knows how many cough droplets), trying to shove a jar of peanut butter in without damaging your 12 pack of eggs. They’re not free range. It’s quantity over morality. You’re sweating, you’re trying to look at the shopping list that you thought would be a good idea on your phone, but the rubber gloves are not working on your touch screen - and should you even be touching your touch screen? If you take them off and touch your touch screen, then bring your phone home, then forget to wash it, then touch your face, or your partner’s, or your garden fence, touched by your elderly neighbour, will you be on your death bed, or theirs, asking yourself whether you really needed to check for the fish sauce for the Thai curry you decided to make because ‘why not learn how to cook during this time?’ said The Guardian article on ‘How to survive the pandemic’, which will ironically now be the death of you and everyone you know. Despite deciding to get out your phone to remember to buy the fish sauce, there is no fish sauce, because it’s a pandemic and you live in West Dulwich. Now you and your partner and your elderly neighbour will die for nothing. Defeated you kick your basket along to the wine isle. You buy four bottles of £5 Merlot and put them under your armpits. One perk of a pandemic is that no one bats an eyelid at this. You no longer care what is on the list. You have alcohol, pot noodles, peanut butter and eggs, this will be enough to survive on until next week, when they’ll surely have fish sauce again. Your self-service checkout predecessor is not even wearing a mask, or gloves, and they coughed once, you note. You try to hold your breath while scanning your items, which have somehow come to £57. You realise you have forgotten to buy chocolate. Chocolate, unlike dried foods, is an essential. Like wine, you will die without it. You apologise to your two successors in the queue and push past them. You stand frozen in front of the chocolate. There's no Dairy Milk. In a panic you choose a £10 Lindt chocolate egg and run back to the machine grasping it like a prize. You feel everyone hates you. Leaving the shop you are triumphant, you pass by the queue with the smug fearlessness of a reality TV contestant who has been voted to stay in the Big Brother House for another week. Until then, you are safe. You have done it. You have survived. Now you can go on the slow, relaxing Mississippi River slide. Although, of course, there is that £10 Lindt Chocolate Egg, touched by so many predecessors before you, those screaming children who demanded it on entry, fingering its luxurious, red wrapping. And you did touch your touch screen, after touching your basket, which touched the floor, which of course, was lifted and dragged and kicked by so many of your predecessors. You rub yourself down with hand sanitiser in a nearby alleyway and, as you squeeze out the last drop, realise you forgot to buy soap, if of course there was any. And soap, like wine, and chocolate, you will die without. You return to the queue, to the very people you passed by before with that smug fearlessness. They all hate you. You smile at the security guard, who cannot see it. You pick up a bag of peas for health. You try to find the soap. |

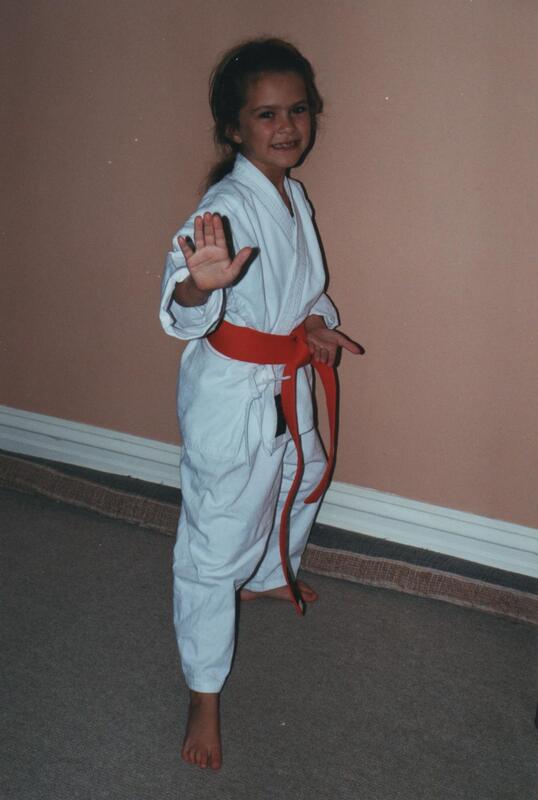

Natalie BeechI am a writer and orange belt in Karate based in London.

A space for things that have no other space. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed